I recently fixed up an old record player from the 70s – the sort that sits inside a large, decorative wooden cabinet with built-in stereo. It was already the nicest piece of furniture I had, but with a new needle and a little care it was purring with the murmurs of vinyl again. I was pleased with how complicated the inner parts were – it had a feature where it could play from a stack of records automatically, one after the other. Where most modern turntables are little more than a piece of stamped plastic with a circuit board, this monolith overwhelmed even me, an (admittedly mediocre) engineer, with its many intermingling mechanisms. I was fortunate that its problems were superficial.

No one would make anything like this today. Although the automatic switching mechanism is somewhat gimmicky and amounts to a clever thought experiment, the copper alone is worth a dozen plastic Chinese turntables. What’s more, a number of parts were carefully machined (machining isn’t conducive to mass production). This was an artifact radiating excess and ingenuity, more closely mimicking the music than the tool. Alternatively, if all machines are music, then most machines are The Disintegration Loops and this one is anything by Bach. It’s not just that “they don’t make ‘em like they used to,” it’s that they don’t even think like they used to.

Efficiency is the zeitgeist of engineering. Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s premier work, Antifragile, connects efficiency to fragility. And, indeed, a close examination of most efficiency improvements reveals associated fragilities. The Federal government has progressively tightened the automotive industry’s fuel economy minimums for years. While an analytic look at the gas combustion cycle shows that even under perfect conditions, a gas engine can only convert 40% of the chemical energy of gasoline into motion, we can also see that such efficiencies are possible only when the cycle is slowed down infinitely. Theoretically, the most efficient engine doesn’t even produce power.

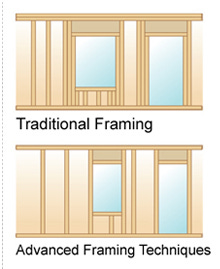

Likewise, consider the construction of houses. The above graphic demonstrates the design differences well: “traditional” (read: old and bad) framing “wastes” material by spacing studs 16 inches center-to-center. “Advanced” (read: optimized) framing spaces studs out to 24 inches, and bolsters the window framing with less material. This is an efficiency technique based on more sophisticated, complex, and presumptuous modeling than we had for the old designs. It necessitates assumptions about wind speed, climate, soil composition, and house layout. It puts incredible weight on what is known and assumes that none of these factors will change over time. But how long will it really last? Will the structure survive long enough to see the builder’s great-grandchildren?

Most mass-consumption product development works this way, whereby with data and analytics, engineers tighten the error margins in their designs and therefore gamble with their products. But thanks to the accepted theory of the product life cycle, which dictates that all products eventually decline in their sales, no one has to build their products to last. The product life cycle does not describe the physical life of the product, but that is nearly the logical conclusion of the doctrine of optimization.

To me, this stinks of the same odor as eating bugs and living in pods. A technocratic ruling class, enlightened with the knowledge of humanity’s dangers and the tools to bring its conformance, wants to dictate the exact living conditions of the individual so that all may live in safety from themselves. The bread has become the circus, no longer bringing true sustenance but only lecherous distraction and the apparition of sustenance. The everyday items we use are implicated in this, becoming worse and more expensive despite the promises of efficiency. This is because they are becoming less human.

Contemporary engineering textbooks would have me believe that to engineer is to optimize. I warrant that to engineer is to build cool stuff.

Image: https://meeksblog.com/2014/03/15/advanced-framing/