I was on my way to college for the first time. I was driving my car I had bought three days earlier, less than three months after I got my drivers license. By all accounts I had no business thinking about much of anything except girls, sports, and being a college freshman. Instead, a wonky bald man had transfixed my imagination. He would ask a question, that warm summer day, which would become my life’s obsession.

How do you respond to declining institutions?

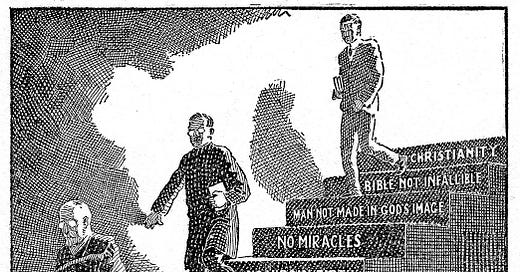

This was accentuated further in my study of the American Fundamentalists at Union. While often quirky in their theological speculation, they were among the first to launch institutional warfare against theological heretics. From my study of them, they determined three major institutions over which the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy was to be fought:

Popular Media

High Culture: They rarely created their own high culture, but sometimes invested in specific parts of culture. For example, Bob Jones, Sr. opened a very notable Baroque art museum at his college, one of the finest personal collections in the Southern United States.

Popular Culture: fundamentalists created some of the most listened-to radio programs in the country, and others like Billy Graham would eventually dominate television as well. The televangelists were usually heretics, but they adapted this system excellently into the 1990s. Even today, preachers like John MacArthur continue this tradition in regular appearances on major news outlets, with followers like Kanye West publishing albums under MacArthur’s influence.

The Church

The Denomination: Frequently denominations had and have governing bodies which act independent of the assembled churches in their midst. These accredit seminaries, vet and ordain pastors, allocate financial resources, support missionary efforts, discipline clergy, and speak to the outside world as a united body. Fundamentalists were very weak at this point, never winning a denominational fight. This had serious repercussions.

The Local Congregation: Fundamentalists were strongest here, as they frequently were powerful and (early on) highly intellectual. They produced thriving churches such as Park Street Church in Boston under Harold Ockenga and a number of congregations in Chicago.

Education

Primary School: This was the least well understood of the education fields by the Fundamentalists. Yet even then there were exceptions, such as R.L. Dabney and Abraham Kuyper (neither of whom strictly counts as a Fundamentalist, but were both heavily influential on the Fundamentalists, particularly their Reformed allies). It would not be until the Reconstructionists of the 1960s and Francis Schaeffer’s work that pre-collegiate education would come under scrutiny, more than forty years after the Scopes Trial.

University: Fundamentalists were very interested in Bible colleges to develop missionaries, train up godly families, and faithful children. Historian Molly Worthen called Wheaton, “a cosmopolitan place. Its worldliness was the approved and godly kind, befitting an oasis where parents sent their children to spare them from the hazards of secular culture and fortify their confidence in the Bible.” Besides Wheaton, other schools like Moody Bible College, Bible Institute of Los Angeles, and Bob Jones were created to replace the Modernist colleges.

To convert those already in the Mainline colleges, Student missions organizations were formed from which large revivals would take place.Seminary: With the denominational seminaries firmly in grasp of the Modernists, Reformed leaders began building seminaries for the ministers. Machen founded Westminster Theological Seminary, while W.H. Griffith Thomas co-founded Dallas Theological Seminary with Lewis Sperry Chafer and matured Wycliffe College, Toronto as an Evangelical Seminary.

Fundamentalists identified these as the grounds on which to defend the family, the country, and the government. Today these are still places of combat between errant modernist theology and historic Christian teaching, but the scope of the conflict has only grown. Neighborhoods, cities, state governments and entire nations are now engulfed in the conflict in a way unimaginable to the early twentieth century fundamentalist.

Enter Aaron Renn. Renn has suggested four major ways of managing institutional decline:

1) Reform: Work from the inside to fix an institution. Advantages: Maintains high loyalty to system, maintains continuity. Disadvantages: Set in existing ways, less autonomy to force reform. Think Wesley and Whitefield’s revivals of the Church of England, or Tea Party take-over of Republican Party. Invest/Defend.

2) Capture or Replace: Buy an existing institution or render it unnecessary through innovation to the larger market. Think Amazon/Silicon Valley, or Henry Ford. Invest/Attack.

3) Withdraw and Restart: Think the OPC, PCA, ECO, Massachusetts Bay Colony. Homeschooling. Divest/Defend.

4) Destroy and Delegitimize: Literally Donald Trump. Destroy the credibility of an organization such that the whole structure no longer poses a threat. This is Divest/Defend.

But most fundamental to Renn’s premise is that decline is actually upon us, and something has to be done. He would readily admit that all of us use all the options given in different aspects of our lives.

With this in mind, there are certain principles from Renn’s analysis which should animate all future projects of Christians, particularly ours.

Chief among this was to save ourselves. My dad always said you can’t save the world if you can’t pay the rent. Others might add “make your bed” or “clean your room.” Our Savior commanded us to love others as ourselves, not instead of ourselves. But even if he did, it is not love to let ourselves become a wreck. It makes us a liability to society, untrustworthy, a parasite to all social environments, and a nihilistic, destabilizing force.

But assuming we are a contributing member of society, it is just as likely that the society is going to be a parasite on you, especially in a declining society. While you cannot entirely escape the guardrails of society, in a culture where the compass is incredibly off-base, applying yourself to the classical virtues of citizenship may well be not just a lost cause, but a suicide cult. Again, this is the other extreme, but if the reader attends to the journalism of Rod Dreher, it is not at all unusual to see tenured professors or editors or employees increasing the social capital of an institution just to be disbarred from the entire industry due to basic Christian beliefs.

In 2022 America, it is industrially foolhardy and intellectually abdicatory to invest in institutions that do not share your loyalties. The exception to this would be where there is a clear pathway to institutional influence, whether a university, school, town, or business which can be reasonably co-opted into our cause and made an ally.

To give an incendiary example, John Calhoun, a notorious secessionist, built the infrastructure for the modern United States army as Secretary of War, which was ruthlessly deployed against his own state only a few decades later in a conflict he imminently feared would occur. Scripture uses the analogy of the arrows and swords of the wicked being turned on themselves, in part because they are blinded by their evil. But righteous idealism can blind just as easily:

“Be not overly righteous, and do not make yourself too wise. Why should you destroy yourself?” -Ecclesiastes 7:16

It is long past time to wake up and realize we are not so much embarking on one-man discipleship projects as we are trading with the Soviet Union. The best interests of Christians are less and less in step with the supposed interests of our society at large, so while we will always maintain some economic relationship with the rest of the world, this must be a time of greater isolation for our spiritual and economic survival. Resisting isolation with excuses about “Evangelizing” or “transforming” the culture through basic market interactions like buying from Amazon can and will be used against us in the courts of time.

Acknowledging decline in major institutions creates a panic which will only create more panic and more withdrawal, which usually forces said declining institutions to protect themselves and attack their critics. This is not a long term solution, but it is surprisingly common. Kodak preferred to ignore and isolate those who warned about advances of cameras rather than jump on the innovation bandwagon. Charles I did not call Parliament until his own destruction was nearly guaranteed. This is not an advantage for the Christian who realizes the decline in society. Almost every prophet was ostracized from their communities. They preached from street corners because they were deplatformed. Declining institutions always have the man-power advantage over those looking to reform or withdraw.

Unless an overwhelming advantage can be gained from their departure, the institution in decline will attempt to punish the dissenter to keep others from jumping ship.

Therefore, effective dissenters must count the specific cost of all institutional battles, whether reform, destruction, or anything in between, and prepare for the consequences of it. To minimize damage incurred from the warfare, we must begin to equip ourselves with the right tools, train to use those tools comfortably before battle begins, and agree amongst ourselves to a set of tactics and rules by which the combat will be waged.

In the coming months, I hope to outline more specific strategies for implementing these aspects of strategy, some helpful tools, and guidelines for our coming war into our lives, families, churches, and commonwealths.