On Circumcision, Antinomianism, and New Life: Part 2

Prelude (Πέρι Λυκειῷ)

Over two years ago, I promised a two-part series exploring the issues of antinomianism and how it relates to circumcision. Since then, despite the whispered murmurings of our critics and the vociferous cries of our supporters, I have not written part two—until today. The world needs this now more than ever, so I’m glad it took this long to publish. It’s time to begin.

In the first essay, I worked through two passages of Scripture in order to establish the question of circumcision and its place for the new people of God. The first was Romans 9:1–18:

It is through Isaac that Abraham’s offspring are named (Gen 21:12; Heb 11:18) and not through Ishmael. Though Ishmael is a son of Abraham by blood, he does not receive the blessings of the covenant promises. The same of Jacob and Esau later on. For God chose Jacob over Esau and then chose Jacob’s twelve sons.1 It is to those twelve through Moses God gave the covenant at Sinai. There he introduced the characteristics which are to define the people of God. After the covenant at Sinai, it appears that God has uniquely called out his people, and all who identify themselves as people of Israel are also people of God. The method by which one could identify themselves—and more importantly, be identified as—part of the people of God was to become part of Israel, and this meant following the Mosaic Law. Even though this reading of God’s call of Israel is understandable, it is fatal, for it misrepresents who the people of God actually are. From God’s point of view, the “people of God” is not synonymous with “people of Israel.”2

This new understanding of who Israel actually is comes into focus here and is essential to understand, looking both forward and backward. If we see that Israel consists of those who have Abraham’s faith and not necessarily those with his blood, then we can understand what circumcision is actually trying to show:

Israel, in Romans and for Paul, now consists of those who have been uniquely called out by faith; they are the elect of God, chosen, not on the basis of their works or their will but on the basis of the one who first called them. It is the remnant of Israel the prophets talked about and the newly grafted-in Gentiles. It is not the seed of Abraham according to the flesh but the seed of Abraham according to the Spirit. It is, in short, those who have been circumcised in their hearts; and circumcision is therefore a sign of faith.

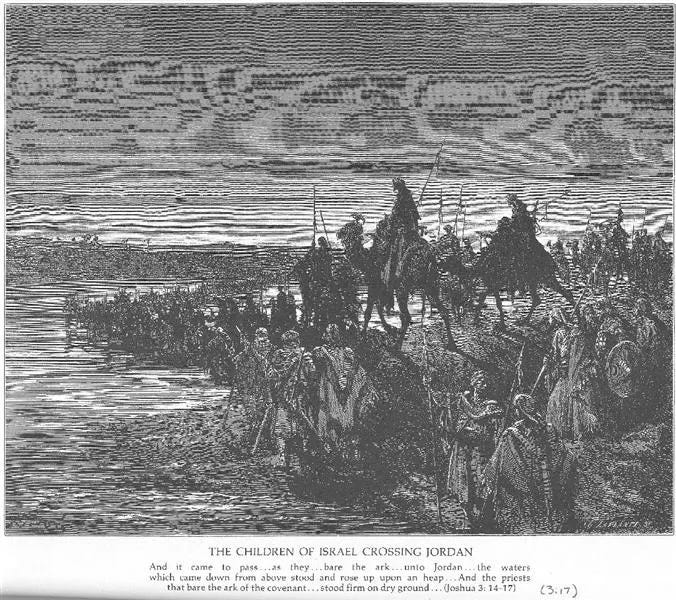

The second passage was Joshua 5:1–12, a passage which describes what happened to the Israelites after the crossed the Jordan River into the Promised Land of Canaan:

In all of life, by taking on the mark of covenant membership (which is faith!), we declare ourselves to belong to the Lord. And therefore, by casting all our hopes on the risen Christ, the one who perfectly fulfilled the law (Matt 5:17–20), we too can receive the benefits of being sons of Abraham: an eternal possession in the Land of Promise (Heb 9:15)…By circumcision, “I have rolled away the reproach of Egypt from you” (Josh 5:9). Covenant renewal takes away the reproach of Egypt because it signifies that Israel is truly God’s people, and that whatever they have done wrong has been redeemed by the Lord.3

While there are many other passages which speak to circumcision and its place in marking out the people of Israel, these two are sufficient to illustrate this point.

Or so I thought. There was one particularly insightful comment:

Is all human action “works”? If so, how can we affirm the “obedience of faith” that Dr. Green has so instilled into us? I'm afraid you're buying into this canned, Lutheran Law-gospel nonsense that's tilting with the windmills of Jeremy Taylor and Origen. You've clearly shown how Wright goes off the deep end (or at least did) in a conference. Great. Now what?4

That question is what we will address in this essay.

About a month after Part 1 was published, I came across another passage which should have been included in the first part. I published my analysis of Galatians 3:10–14 in an interlude. Using Septuagint Habakkuk 2:4, the Qumran commentary (1QpHab 7:17–8:3; 4QpNah1:17–18), and a plain reading of Deuteronomy and Galatians, I provided further evidence that faith alone allows us to escape the “curse of the law” since Jesus became a curse for us by “hanging on a tree”:

Paul suggests that all those who wish to be justified by the law are actually under a curse, for the one who wishes to live by the law must keep the whole law. But the one who is righteous lives by means of faith, escaping the curse of the law through the death of Jesus Christ. Christ died on a tree so that “we” (inclusive) would be free from keeping the obligations of the law. And as a result of this, and even for this purpose Christ died: that the Gentiles might be included in the covenant family and that the promised Spirit might come as a seal of salvation to all those who are made righteous by faith.

New life is not connected to our obedience to the law but to Jesus’ death. We become participants in his death by our own death (Gal 2:20) so that we may be raised to newness of life. We die to ourselves daily only by faith.

This essay is the long-awaited sequel to conclude this argument to explain its relevance for our present age. As explained above, I approached the question of circumcision indirectly, first with an analysis of three scriptural passages (Romans 9:1–18; Joshua 5:1–12; Galatians 3:10–14); while I promised to offer a critique of the common reading of circumcision as a “boundary marker” like the food code, an already overly-long and therefore overly-taxing first essay (and subsequent interlude) demanded that I postpone that argument until the second one. Therefore, the primary thesis of this essay will be to advance the argument that circumcision must be thought of as a fundamental part of the covenant made, not with Moses, but with Abraham. In this sense, as Paul says in Galatians 4 and Romans 9, those who are circumcised in their hearts are counted as sons of Abraham. This means we must also address the apparent contradiction between James and Paul by refuting both heresies of antinomianism and legalism, which are tightly bound up with the issue of circumcision.

How to Read the Bible

Before any of that, however, I need to briefly explain how I read the Bible. There are two key assumptions relevant throughout this essay:

The Bible is cohesive, unified, and speaks with one voice. While recognizing the distinct and unique voices of the various human authors, all of the Bible is the Word of God. This means we can and should use one part of Scripture to understand another part. We make no part of Scripture repugnant to another, believing it all to be necessary and sufficient to provide guidance by which men may be saved.

Only those who believe in something may truly and fully understand it. The roots of this are with Saint Anselm in the eleventh century (credo ut intelligam), but it is articulated most powerfully by Hans-Georg Gadamer in the twentieth, who suggests prejudice is a precondition of genuine understanding.5 Secular biblical scholars have their place, and they have much to teach us. However, we are not obligated to accept their conclusions as authoritative because they do not actually believe what they are studying and so incapable of truly understanding it.

Anselm sees this as well in chapter 1 of the Proslogion:

Teach me to seek you and reveal yourself to me, when I seek you, for I cannot seek you, except you teach me, nor find you, except you reveal yourself…For I do not seek to understand that I may believe, but I believe in order to understand. For this also I believe, —unless I believed, I should not understand.

Assumption 1 is more important but also more difficult to prove. The devil has, through the secular and atheistic “Academy,” taken every opportunity to undermine people’s confidence in the trustworthiness of the Word of God. While I cannot lay out every demonstrable proof here, I can say that the Christian church has always held two key beliefs about Christian biblical interpretation; from this perspective, I am in good company:

There is basic coherence between the Old and New Testaments since ALL Scripture points to Jesus;

Interpretation is subject to the regula fidei, meaning interpretation is always in the context of the Church and in service to the Church.

As Augustine teaches, “The end of all holy Scripture is the love of an object to be enjoyed” (De doc. Chr. 1.39). To use it for another end—for cultural analysis, for mythographical survey, for civilizational conquest—is a categorical mistake. If we use Scripture for anything other than the means by which we learn to enjoy God himself, then we do disservice to the Bible and harm to ourselves. The Schoolmen understood this as well, for they believed the Word of God has the power to transform the human soul. The Bible was written for intellectual truth, but its primary purpose is for moral transformation. The study of the Bible is a means of grace.

What is the Gospel?

The key insight of the Reformation was the promulgation of a revived view of righteousness. The Schoolmen taught, following Aristotle, that we become good by doing good. Luther insisted that the theology of the Cross alone could conceptualize our place in the world correctly, for “philosophy outside the grace of Christ is the perverse love of knowing” (perversus amor sciendi) (WA 59:410, 2–3). For Luther and the Reformers, Aristotle’s influence on the Medieval Church meant they “philosophize outside of Christ[, which] is the same as fornicating outside of marriage” (410, 10–11). In Heidelberg Disputation 29, Luther says, “Whoever wishes without danger to philosophize using Aristotle must beforehand become thoroughly foolish in Christ.” Citing 1 Corinthians 1, he says that philosophy has only inflated the egos of men who believe they can justify themselves. As Dennis Bielfeldt explains it, from Luther’s perspective, “The heavenly has its own logic of grace that illuminates human standing before God—both in the moral and epistemological orders.”6 Rather than hoping for Christ the Judge to weigh our souls and be found sufficient, Luther believes we have freely received God’s free and gracious gift of salvation only by faith. Though this contradicts the natural human inclination toward self-justification, the “righteousness of God” Paul speaks of (Rom 1:16–17) is given to those who are “in Christ” (Gal 2:20).

Men are saved by the Word of God which produces faith (Rom 10:14–15), and faith works itself out through love (Gal 5:6). Rather than love being a precondition for salvation, love is the final fruit of it. The righteousness of God is freely given to those who hear and believe the Word, for only those who hear may believe, and only those who believe may truly love.

And this is the significance of the Scriptures. The Scriptures are the primary means by which God speaks to us. While we do not believe with Schleiermacher that religion is a feeling of absolute dependence, and the Bible is a detailed expression of the faith that satisfies our need to feel absolutely dependent, we do believe that the Bible is written for us so that we may believe (Jn 20:31). But without an overarching narrative or doctrinal unity, “the Bible cannot compete with the imperial present” (Timothy George, Reading the Bible with the Reformers). The purpose of the Scripture is for knowledge, and we need to understand the Bible with our mind to grasp its significance, its constant act of speech, and that we are not the focus of the story of the world. But more than that, the Bible teaches us how we may be righteous before God. Jesus appeared directly to Saint Paul (Ac 9:4–6; 23:11) and then taught him the true message of the Gospel, the Word which he was to preach to the nations (Gal 1:11–12, 17–18). While we do not yet see the risen Christ, we are made righteous by his blood, fully assured that we have received the righteousness of God by faith and so are made righteous in his sight (Jn 20:29; 2 Cor 5:7). This is no “legal fiction,” for the Word of God is always effective. God creates the world out of nothing by speaking; he too creates new life in us by the power of his Word. I do not become good by doing good, as Aristotle teaches; I become good because God has declared, “It is good.”

Antinomianism & Legalism: Our Two Modern Heresies

Given the powerful message of the gospel, there are two easy errors into which we can slip. The first is to cheapen the law, and the second is to cheapen grace. But in cheapening one we cheapen the other, for the good news cannot be heard without first hearing the condemnation of the law, and the law only condemns; it cannot give life. As Luther says, Christ is not “a new lawgiver [but] the son of God, who…because of his sheer mercy and love, gave and offered himself…for us. He is not Moses…or a lawgiver; he is the dispenser of grace, the savior,” [the] “joy and sweetness of a trembling and troubled heart” (LW 26.176–177). In Master Patrick’s Places recorded in Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, it says, “The law says where is your righteousness? The gospel says Christ is your righteousness” (8.3, p. 1150).7 If the message of the gospel is that we can receive the righteousness of Christ by faith, then the message of the law must be that we cannot receive the righteousness of Christ in any other way.

There are two particular errors into which we can fall when we misunderstand the gospel. The first is antinomianism, which is a cheapening of the gospel. This is James’ concern when he says, “What good is it, my brothers, if someone says he has faith but does not have works? Can that faith save him?…You see that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone” (Ja 2:14–26). The antinomians believe they are exempt from the law; now that they are free in Christ, there is no “ought” which compels them. Setting aside the law, the antinomians believe that Christians are free to do as they wish because they have believed in the gospel.8 Luther wrote six treatises against the antinomians in which he argued they misunderstood the “third use of the law”: to show Christians what they ought to do.

The Anglican Church affirms this as well in Article 7: “Although the Law given from God by Moses, as touching Ceremonies and Rites, do not bind Christian men, nor the Civil precepts thereof ought of necessity to be received in any commonwealth; yet notwithstanding, no Christian man whatsoever is free from the obedience of the Commandments which are called Moral” (cf WCF 19). When Paul says we are not justified by keeping the law (Gal 5:4), he tempers this with his statement “we uphold the law” (Rom 3:31). However, this is no “get in by faith, stay in by works” arrangement. We are not counted as members of the covenant family by grace but maintain our status as God’s children by our good works for him. This is why Paul says in Romans, “Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound? By no means!…just as Christ was raised from the dead by the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Rom 6:1–4). While James is a bit crasser, both Paul and James emphasize that new life in Christ, which is freely given from above (Ja 1:17), means too the death of the old self and its sinful desires (Col 3:5–10). While this does not mean we will be perfect in this life, it does mean that those who do the will of God will abide forever (1 Jn 2:17), and to do God’s will means only to believe in “the one he has sent” (Jn 6:29).

The second is legalism, which is a cheapening of the law. This is a far more insidious problem than antinomianism. For antinomianism is easy to condemn on the surface for Christians, especially those who believe in the Scripture and desire to retain their institutions. Legalism, however, is to say we are justified in God’s sight by our own efforts. Such an idea is foolish, as we have already explained, for “no one does good” (Ps 14:3; Rom 3:12). Though we are capable of performing acts which are morally right, it does not follow from that we are righteous in God’s sight, for our best “acts are like filthy rags” (Is 64:6). This is true before we are justified and after, for the good I do is God in me: “For this I toil, struggling with all his energy that he powerfully works within me” (Col 1:29); again, “it is God who works in you” (Phil 2:13), and Galatians 2:20: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” Every piece of salvation, from our first justification to our final, is a gift of God and completely his work of grace. For salvation is resurrection, and who can give life to the dead but God alone?

The antinomians and the legalists both misunderstand the purpose of the law in Luther’s theology of the cross, for he says that living faith is

a living, creative, active and powerful thing, this faith. Faith cannot help doing good works constantly. It doesn’t stop to ask if good works ought to be done, but before anyone asks, it already has done them and continues to do them without ceasing. Anyone who does not do good works in this manner is an unbeliever…Thus, it is just as impossible to separate faith and works as it is to separate heat and light from fire!9

As the children of God, we know we are righteous by the obedience of faith. This is not obedience to the law but the outpouring of faith working through love (Gal 5:6), which is Christ working in us (Phil 2:13).

The Sign of Circumcision: New Life in a New Land and the Status of the Law

It is now time to make sense of the sign of circumcision. Circumcision is a sign of membership in the covenant community, which is why it has been linked by the Presbyterians to baptism. Their arguments for that link are persuasive and do not bear repeating here. On that basis, then we can say with full confidence that baptism is the sign of covenant membership and of inclusion as a child of God. Baptism is not a work since it is God working in us. Circumcision which saves is the circumcision of the heart (Rom 2:29; 3:10–18; cf 1 QS 5:5). Circumcision as a work is not commanded in the law, for it is not a sign of the Mosaic covenant. In fact, it has nothing to do with the law at all. It is the sign of the Abrahamic covenant, which means that all who desire to be “sons of Abraham” and thereby become sons of God, receiving the kingdom of heaven and accomplishing God’s will on earth, must be circumcised. This circumcision is baptism, yes, but it is far more than that. It is faith that, as God was faithful in the past he will be faithful again; it is love for our Triune God and for the world he has made; it is hope, ever forward-looking to receive the kingdom prepared for us from the beginning of the world. This is new life in a new land! The circumcision of the heart is how we know our “labor is not in vain” (1 Cor 15:58).

The book of Ezekiel is particularly grim as it announces God’s judgment against his people. Over and over again, God has extended grace to Israel, calling them his chosen possession and beloved bride, but Israel has preferred to play the harlot, and abandoning the God of life has resulted in Israel’s death. But God is not done with Israel. Into the dry bones of the long-dead people of Israel God sends his Spirit, and that Spirit brings new life into their weary souls. God pronounced judgment against the Jews for nearly 36 chapters. The invectives are ongoing and devastating. Israel will receive the full weight of God’s wrath because of her faithlessness—not because of her inability to keep the law, but because of her lack of faith in the God who gave it to them. This ends in chapter 36 with a condemnation of the “mountain of Israel,” which is a shorthand way to refer to the entire nation of Israel itself. The “mountain” of Israel is Israel—when God brings down judgment on the mountain of Israel, it means that Israel has been leveled, that it is no more, that it has no hope of resurrection.

AND YET. “It is not for your sake, O house of Israel, that I am about to act, but for the sake of my holy name” (Ezek 36:22). What is the thing that God is going to do? He is going to bring back the people of Israel from where they have been scattered all over the face of the earth. The land that was desolate shall become like the Garden of Eden; the houses that were empty shall be filled again; the cities that were ruined shall again be fortified and inhabited. This is the turning point of the book of Ezekiel, when God promises to cleanse his people with water and put his Spirit in them—to give them a new heart.

Right after Ezekiel 36 is the most famous passage in the book—the story of the dry bones. “Can these bones live,” the Lord asks. The answer is an emphatic YES. Though no one in their own power could grant life to dry bones, the Spirit of the Lord can give life to those who were previously dead. And the blessings are the promise of a Davidic king who shall be a good shepherd. Here we have references to John 10—Jesus claims to be the “good shepherd,” and in so doing declares himself to be the forever-ruling Davidic king: “My servant David shall be king over them, and they shall all have one shepherd. They shall walk in my rules and be careful to obey my statutes. They shall dwell in the land that I gave to my servant Jacob, where your fathers lived. They and their children and their children's children shall dwell there forever, and David my servant shall be their prince forever” (Ezek 37:24–25).

After new life is given to the previously-dead army of God, they rise up and defeat Israel’s enemies, personified by the wicked king Gog. Then, Ezekiel receives a vision of a new temple. In this temple, the Lord lives with and loves his people forevermore. In this temple, God has fully restored Israel and given her “infinitely more” than she “can ask or imagine.” At the general resurrection on the last day, your righteousness and good works are not enough to grant you admission into eternal life. It is faith in the Lord Jesus which alone can give you new life. And the blessing Jesus shall pronounce upon all those who love and fear him: “Come, ye blessed children of my Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you from the beginning of the world.” Grant this, we beseech you, O merciful Father, through Jesus Christ our mediator and redeemer.

I tilt at the windmills of Jeremy Taylor and Origen, praying that one day enough join me for their windmills to finally collapse. Ut in omnibus glorificetur Deus, et semper super firmum fundamentum Dei: AMDG, amen.

All the twelve sons of Jacob receive the covenant blessings except for Dan (Rev 7:5–8). Is this punishment for his wickedness during the time of the Judges?

See Ellis W. Deibler, Jr., A Semantic and Structural Analysis of Romans (Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics, 1998), 213.

See John Calvin, Commentaries on the Book of Joshua, trans. Henry Beveridge (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1949), 82.

Bradley G. Green is Professor of Theological Studies at Union University and Visiting Professor of Theology and Philosophy at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. My response to this comment included references to Scripture (Ac 13:38–39; Rom 3:19–22; 8:3–4; Gal 2:15–16; 3:24) and this observation: “It is an unspeakable comfort to hear what our Lord Jesus Christ says: ‘Come unto me all ye that travail and are heavy laden, and I will refresh you.’ It is Christ at work in us and through us. In some sense, and we'll get into this a bit in the second part, there are two natures in us: ourselves, the ‘I’ of ‘I do not do what I want to do but the thing I hate,’ and Christ, the ‘not I’ of ‘yet not I, but through Christ in me.’ Until the I is totally transformed by the not-I, it is incapable of fulfilling all the demands of the law.”

“Long before we understand a text in detail, we already have a vague idea of its meaning as a whole. It is a circular relationship: the anticipation of meaning in which the whole is envisaged becomes explicit understanding only through the understanding of the parts that are determined by the whole. All understanding inevitably involves some prejudice”; in Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall, 2nd rev. ed. (New York: Continuum, 2004), 269. Gadamer says that, since all people approach an issue or text with prejudgments (Vorurteile) and pre-understandings (Vorverständnis), there is no neutral observation, no unbiased judgment. A prejudice is an enabling condition of understanding, but true understanding happens only when our prejudices are open to modification based on the findings of interpretation itself.

Dennis Bielfeldt, “Introduction to Heidelberg Disputation, 1518,” in The Annotated Luther, Volume 1: The Roots of Reform, ed. Timothy J. Wengert (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2015), 79.

John Foxe, The Unabridged Acts and Monuments Online or TAMO (1570 edition) (The Digital Humanities Institute, Sheffield, 2011). Available from: http//www.dhi.ac.uk/foxe [Accessed: 10 June 2025].

August L. Graebner, “Antinomianism,” in The Lutheran Cyclopedia, eds. Henry Eyster Jacobs and John A. W. Haas (New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1899), 18.

Martin Luther, “An Introduction to St Paul’s Letter to the Romans,” in Vermischte Deutsche Schriften, vol. 63, ed. Johann K. Irmischer, trans. Robert E. Smith (Erlangen: Heyder & Zimmer, 1854), 124–125.