For whatever reason, the English like to do things differently. European Union? Try Brexit. Continental Rationalism? Try British Empiricism. Drinking coffee? Try tea. Getting crushed by Napoleon? Try winning instead. One such instance of difference comes through poetry. Compare the comic poets Dante and Chaucer. Dante’s comedy works at the eschatalogical level. Chaucer, on the other hand, is rather down to earth. The English imagination loves the particulars. God made the world, and despite its fallenness, it is to be loved. Ascetic removal from the world amounts to a rejection of the Creator.1

One of the things which Chaucer and Dante both signal is the corruption of monasticism. It was England, however, whose Reformation dealt with this corruption at a scale yet unseen historically. In his efforts to establish an independent English church, Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries across Britain.2 While the dissolution of English monasteries served political and ecclesiastical purposes primarily, it also reflected, whether Henry intended it or not, a theological emphasis of the Protestant reformation. Whereas medieval Catholicism exalted monastic or priestly vocations as superior to others, critiques of monasticism by the Reformers suggest that such exaltation misses the mark of Christian life and eschatology. Instead, these Reformers reaffirmed the significance of every calling as performed under grace. Life under grace transforms all work into Kingdom work.3

Despite the political motivations behind the dissolution of monasteries, the move at least reflected a theological shift away from monastic life as practiced through the Middle Ages. However, monasticism did not disappear, especially in the English tradition. The installation of the Book of Common Prayer reflected a kind of bridge between cenobitic prayer and the commoner. The rigorous schedule of prayer from the monastery is not practicable for the farmer or tradesman. The Book of Common Prayer, with its two daily offices, brought the ideal of ritualized prayer to the lives of ordinary people. We might say that the dissolution of monasteries in England gives way to the “monasticizing” of all.

However, a different kind of monasticism emerged out of the Reformation as well. This new form of monasticism finds the cloistered academic in the safety of his university, largely disconnected from the rest of the world. The “ivory tower” academic finds his roots somewhere between the universities of the late middle ages and cenobitic monasticism. At their best, monks retained a connection to their communities through service. If such service is neglected, the monks lose connection to the concerns of the rest of the world. The “ivory tower” or “cloistered” academic runs the same risk. He might be an extension of the Protestant emphasis on all kinds of work. However, if the monk runs the risk of being so heavenly minded that he is of no earthly good, the academic runs the risk of being so esoterically minded that he is of no earthly good. The rise of the German research university in the 19th century and increasing attention to specialization contributed to the problem.

As it would happen, in their philosophical endeavors, the English retained their attachment to the physical world. While the Continental Rationalists emphasized the ideal in their philosophy, the British Empiricists firmly committed to experience and common sense as the foundation for philosophy. The philosophical tendencies of the Island and Continent again reflect the difference between Chaucer and Dante. Even as philosophy in both places becomes increasingly esoteric, the British at least keep a closer connection to the experienced world.

British Empiricism would play a hand in the American Founding. John Locke, an early empiricist, would have a significant hand in the American founding via Thomas Jefferson.4 George Berkeley lived in America for some time, and had connections to Yale and Columbia.5 David Hume was read among the colonists and found his way into the American founding.6 It makes sense that the philosophies from England would make their way to the Colonies, finding ready ears to hear. However, the tendency of empiricism to begin with experience and common sense already existed in America.

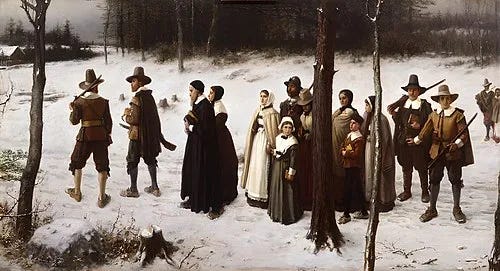

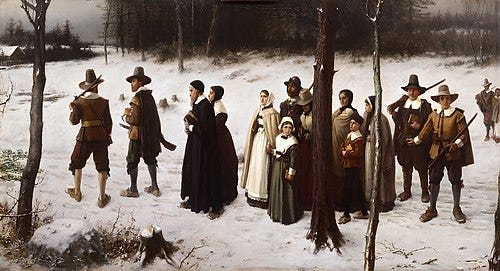

Education in the new world could not afford much of the content and manner of European education. This was in large part due to the nature of colonial life: much more attention was given to survival. Incidentally, the Puritan disdain for recreation was due to the fact that there simply wasn’t time to waste…recreation distracted from the work required to survive, which was a group effort. The emphasis on survival demanded that education be practical: those things necessary for life and salvation. Learn to pray, learn to plow. Thus, colonists were, in a sense, empiricists by necessity. The English attention to the created world, if not consciously carried over, was adopted for survival value.

With the Puritans, we find the English synthesis of monasticism and everyday life in the Colonies. The Puritan desire for religious freedom (which brought them to the new world) together with their rigorous work ethic created a new kind of ora et labora. The Puritan or Protestant work ethic, inseparable from religious life, may be the best Protestant response to monasticism, or perhaps at least the English response. So where did it go?

By the time of the American founding, growing cities had allowed for a new aristocracy. Nevertheless, America retained an agrarian spirit, and early American writings reflect a tension between the liberal tradition received from England and the practical needs of the new nation. Among others, Washington expresses the sentiment that a republican government demands universal education.7 Universal does not mean equal. The Founding Fathers were well aware that different offices necessitated different educations; the farmer’s education will differ from the statesman’s, etc. Nevertheless, a liberal nation demands a liberal citizenry, and liberal citizenry demands liberal education.

The history of American education is an experiment in liberal education for all, particularly in a nation which, in its roots, was deeply tied to agrarian culture. If the Puritan mode of work and prayer represents the proper Protestant monasticism, then the cloistered academic represents post-protestant or secular monasticism. The cloistered academic is exactly the kind of person I suspect the Founding Fathers wished to avoid. We might even add to the category of cloistered academic, the cloistered politician, the cloistered executive, and the cloistered technocrat. Of such men, I suspect the Founding Fathers would have little praise.

Perhaps the Puritans are the best model for a Protestant response to monasticism. We do not necessarily need to disband the university; we could certainly reform it. The Puritan ora et labora provided the work ethic which allowed America to become great over the last centuries; a departure from the union of work and prayer has left America in stagnation. Our sad parody of monastics are blissfully separate from the people they exploit while purporting to serve. Maybe we should make community service a mandatory part of college education. Maybe we should require every American to work on a farm for a year while reading Chaucer. It would certainly cultivate appreciation for the earth, a particularly English inheritance we would do well to preserve.

I once made a derogatory comment about a cow or horse, to which my sister replied, “God loves it, and you should too.” It bothered me, because I knew she was right, and that an hour spent on horseback or shoveling horse poo would supplement my master’s degree more than adding another book.

Content on Chaucer and Dante from Dr. David Whalen’s lectures on Chaucer. EDU 622: Humane Letters II, Hillsdale College, January 2025.

Jack Waters, “A Man for Our Season.” The American Reformer, March 24, 2023. https://americanreformer.org/2023/03/a-man-for-our-season/

Dan Doriani, “The Power––and Danger––in Luther’s Concept of Work.” The Gospel Coalition, May 16, 2016. https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/the-power-and-danger-in-luthers-concept-of-work/

George Stephens, “John Locke: His American and Carolignian Legacy.” The John Locke Foundation. https://www.johnlocke.org/john-locke-his-american-and-carolinian-legacy/

Brian Duignan, “George Berkeley.” Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Berkeley/Period-of-his-major-works

Robert Case, “David Hume at the Constitutional Convention.” Law and Liberty, November 8, 2022. https://lawliberty.org/david-hume-at-the-constitutional-convention/

George Washington, “From George Washington to Robert Brooke, 16 March 1795.” National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-17-02-0443

Good piece Sam